Those who have seen the Shanghai and Hongkong films of Wong kar-wai, have likely been appreciating, without knowing it, the colour palette of cinematographer Chris Doyle, an Englishman working in China, and a diviner of eras as no other cameraman. He deserves his own post, but I am still hanging on Natasha. In my pursuit of a greater appreciation of her work, I have been dabbling in her films, all of which teach me how utterly underrated this actor has been, by me and by the world, and how sad that I myself am only gaining the full knowledge of this as a result of her death. She was incredibly gifted and while I still stand behind my fondness for her in

The Parent Trap (see earlier post), there are so many other riches.

More recently, I have been absorbed by

The White Countess, a film which has an astonishing amount of layered meaning going on within performances and within the construction of the thematic development of the film itself. Richardson plays an exiled Russian countess who does taxi turns in a shabby dance hall to support her also-exiled family. Written by Kazuo Ichiguro with lovely touches of humour and spare splashes of narrative (wisely never allowing 'story' to be driving), this Merchant Ivory production might easily have succumbed to a burdensome fancifulness of context: Shanghai in the between-the-wars melting pot of the 1930s, where deposed Russian nobility live and work side by side with Jewish merchants escaping rising anti-Semitism in Europe. However, the lushness of cinematographer Chris Doyle's visual style, and the patiently detailed direction of James Ivory keep the film in a kind of trance-like combination of realism and dreamworld.

They are ably assisted by Redgrave royalty as the burnished victims of Bolshevism: besides Richardson herself, Vanessa and Lynn Redgrave play members of the Countess' extended family, people whose delusion and despair have turned them into rather nasty, or simply saddened people. (Though it is unquestionably Natasha's movie, both Redgraves earn their keep with a memorable scene each: Lynn in a turn of exquisite cruelty as she explains to Richardson why she will be left behind in the exodus from Shanghai that ends the film; and Vanessa in a moment where she offers Richardson a 'soft' pillow for her to sleep on after a hard night's work.)

Ralph Fiennes plays an American survivor of equally tragic circumstances, made blind by an accident that killed someone close to him. Once a 'diplomatist', he is now a wealthy man-about-town, drowning his losses in alcohol and dreaming of his own big bar/nightclub. Circumstances introduce him to the countess, whom he later positions as the 'centerpiece' of this new bar. The two have a wonderfully unconsummated but loaded relationship: deeply mutually respectful and kind, while also frustratingly unfulfilled, simply because of how dissipated they are by their own losses. What a wonderful diversion from more typical boy-meets-girl scenarios of most North American films. The need of Fiennes' 'Mr. Jackson' to keep everything anonymous between them, slowly wears thin as he himself falls hopelessly in love with his club's leading lady. His unrecognized passion is revealed in sudden fits of possessive temper, when he bounces from his bar characters who are relatively benign in the corrupt scheme of this world, merely for having offended Sofia's honour.

Richardson's Sofia remains aloof throughout, as if she herself is one of the battered boats our characters escape on in the film's final sequence with a faded but unfettered elegance. She is amazing in this film. There is a brooding in the eyes that reveals the deepest pain, even while showing pleasure in simple joys. It is as if the pleasure and the momentary pain go hand in hand. It is a remarkably observed detail of character that flows right out of a desire (expressed in the movie's commentary) for nuancing a Russian sensibility. Having written about Russians myself, and known a few, this is exactly the quality worth striving for. It means that a character's deep sadness and equally her capacity for happiness are never in dispute. One scene which captures this duality with absolute brilliance occurs when someone from her old world in Russia, now himself reduced to bussing bottles and clearing tables, recognizes the countess in the club. Approaching her with the utmost respect, he reminds her of their childhood times together playing tennis. The slow recognition on her face, the movement through beats of uncertainty to amazement, to joy, to tragic sadness again as he kisses her hand to leave, are breathtaking. The brimming brooding eyes as he moves away speak vividly to all of her losses. It is a master class of "beat" work!

The character who ultimately unites our two lost souls is Katya, the daughter of the countess, whose bright alertness to her world makes her an easy pawn in her family's dynamics but also enables her to be freed from them in the end. Played by Madeleine Daly, her red-headed narrow face seems a more likely offshoot of Grushenka, played by Madeleine Potter, the countess' sister-in-law, who is childless and tries hard to drive wedges between mother and daughter. Katya walks through all the worlds of this film: though never seen in the nightclub, she does meet up with and befriend the Fiennes character, and reminds him of his own lost child. She also provides a tie to the other social world of this film which is a family of Jewish immigrants to Shanghai, whose children are a more natural source of companionship for her than her strange family. This exposure helps give her a worldliness that fully ennobles one of the last shots of the film, as she stands staring off the prow of a ship into her own future.

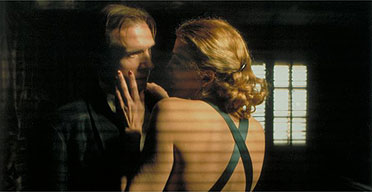

This image at left comes from that same last scene. It represents one of the few moments of near-happiness and transcendence that exists in this film. Our tragedy-sodden characters only find solace with each other through another tragedy, which is the end of the world as they were living it. This is often how it is in life: it often does take the utter decimation of the static place in which we have cemented ourselves, to push us forward, kick us out of the trenches of our own pain. On a boat bound for Macao our characters huddle in the mist and listen to the sounds of a forlorn but hopeful trumpet, now free of the baggage of what was, and off on a new voyage.

Those who have seen the Shanghai and Hongkong films of Wong kar-wai, have likely been appreciating, without knowing it, the colour palette of cinematographer Chris Doyle, an Englishman working in China, and a diviner of eras as no other cameraman. He deserves his own post, but I am still hanging on Natasha. In my pursuit of a greater appreciation of her work, I have been dabbling in her films, all of which teach me how utterly underrated this actor has been, by me and by the world, and how sad that I myself am only gaining the full knowledge of this as a result of her death. She was incredibly gifted and while I still stand behind my fondness for her in The Parent Trap (see earlier post), there are so many other riches.

Those who have seen the Shanghai and Hongkong films of Wong kar-wai, have likely been appreciating, without knowing it, the colour palette of cinematographer Chris Doyle, an Englishman working in China, and a diviner of eras as no other cameraman. He deserves his own post, but I am still hanging on Natasha. In my pursuit of a greater appreciation of her work, I have been dabbling in her films, all of which teach me how utterly underrated this actor has been, by me and by the world, and how sad that I myself am only gaining the full knowledge of this as a result of her death. She was incredibly gifted and while I still stand behind my fondness for her in The Parent Trap (see earlier post), there are so many other riches.  More recently, I have been absorbed by The White Countess, a film which has an astonishing amount of layered meaning going on within performances and within the construction of the thematic development of the film itself. Richardson plays an exiled Russian countess who does taxi turns in a shabby dance hall to support her also-exiled family. Written by Kazuo Ichiguro with lovely touches of humour and spare splashes of narrative (wisely never allowing 'story' to be driving), this Merchant Ivory production might easily have succumbed to a burdensome fancifulness of context: Shanghai in the between-the-wars melting pot of the 1930s, where deposed Russian nobility live and work side by side with Jewish merchants escaping rising anti-Semitism in Europe. However, the lushness of cinematographer Chris Doyle's visual style, and the patiently detailed direction of James Ivory keep the film in a kind of trance-like combination of realism and dreamworld.

More recently, I have been absorbed by The White Countess, a film which has an astonishing amount of layered meaning going on within performances and within the construction of the thematic development of the film itself. Richardson plays an exiled Russian countess who does taxi turns in a shabby dance hall to support her also-exiled family. Written by Kazuo Ichiguro with lovely touches of humour and spare splashes of narrative (wisely never allowing 'story' to be driving), this Merchant Ivory production might easily have succumbed to a burdensome fancifulness of context: Shanghai in the between-the-wars melting pot of the 1930s, where deposed Russian nobility live and work side by side with Jewish merchants escaping rising anti-Semitism in Europe. However, the lushness of cinematographer Chris Doyle's visual style, and the patiently detailed direction of James Ivory keep the film in a kind of trance-like combination of realism and dreamworld.  They are ably assisted by Redgrave royalty as the burnished victims of Bolshevism: besides Richardson herself, Vanessa and Lynn Redgrave play members of the Countess' extended family, people whose delusion and despair have turned them into rather nasty, or simply saddened people. (Though it is unquestionably Natasha's movie, both Redgraves earn their keep with a memorable scene each: Lynn in a turn of exquisite cruelty as she explains to Richardson why she will be left behind in the exodus from Shanghai that ends the film; and Vanessa in a moment where she offers Richardson a 'soft' pillow for her to sleep on after a hard night's work.)

They are ably assisted by Redgrave royalty as the burnished victims of Bolshevism: besides Richardson herself, Vanessa and Lynn Redgrave play members of the Countess' extended family, people whose delusion and despair have turned them into rather nasty, or simply saddened people. (Though it is unquestionably Natasha's movie, both Redgraves earn their keep with a memorable scene each: Lynn in a turn of exquisite cruelty as she explains to Richardson why she will be left behind in the exodus from Shanghai that ends the film; and Vanessa in a moment where she offers Richardson a 'soft' pillow for her to sleep on after a hard night's work.)  Ralph Fiennes plays an American survivor of equally tragic circumstances, made blind by an accident that killed someone close to him. Once a 'diplomatist', he is now a wealthy man-about-town, drowning his losses in alcohol and dreaming of his own big bar/nightclub. Circumstances introduce him to the countess, whom he later positions as the 'centerpiece' of this new bar. The two have a wonderfully unconsummated but loaded relationship: deeply mutually respectful and kind, while also frustratingly unfulfilled, simply because of how dissipated they are by their own losses. What a wonderful diversion from more typical boy-meets-girl scenarios of most North American films. The need of Fiennes' 'Mr. Jackson' to keep everything anonymous between them, slowly wears thin as he himself falls hopelessly in love with his club's leading lady. His unrecognized passion is revealed in sudden fits of possessive temper, when he bounces from his bar characters who are relatively benign in the corrupt scheme of this world, merely for having offended Sofia's honour.

Ralph Fiennes plays an American survivor of equally tragic circumstances, made blind by an accident that killed someone close to him. Once a 'diplomatist', he is now a wealthy man-about-town, drowning his losses in alcohol and dreaming of his own big bar/nightclub. Circumstances introduce him to the countess, whom he later positions as the 'centerpiece' of this new bar. The two have a wonderfully unconsummated but loaded relationship: deeply mutually respectful and kind, while also frustratingly unfulfilled, simply because of how dissipated they are by their own losses. What a wonderful diversion from more typical boy-meets-girl scenarios of most North American films. The need of Fiennes' 'Mr. Jackson' to keep everything anonymous between them, slowly wears thin as he himself falls hopelessly in love with his club's leading lady. His unrecognized passion is revealed in sudden fits of possessive temper, when he bounces from his bar characters who are relatively benign in the corrupt scheme of this world, merely for having offended Sofia's honour.  Richardson's Sofia remains aloof throughout, as if she herself is one of the battered boats our characters escape on in the film's final sequence with a faded but unfettered elegance. She is amazing in this film. There is a brooding in the eyes that reveals the deepest pain, even while showing pleasure in simple joys. It is as if the pleasure and the momentary pain go hand in hand. It is a remarkably observed detail of character that flows right out of a desire (expressed in the movie's commentary) for nuancing a Russian sensibility. Having written about Russians myself, and known a few, this is exactly the quality worth striving for. It means that a character's deep sadness and equally her capacity for happiness are never in dispute. One scene which captures this duality with absolute brilliance occurs when someone from her old world in Russia, now himself reduced to bussing bottles and clearing tables, recognizes the countess in the club. Approaching her with the utmost respect, he reminds her of their childhood times together playing tennis. The slow recognition on her face, the movement through beats of uncertainty to amazement, to joy, to tragic sadness again as he kisses her hand to leave, are breathtaking. The brimming brooding eyes as he moves away speak vividly to all of her losses. It is a master class of "beat" work!

Richardson's Sofia remains aloof throughout, as if she herself is one of the battered boats our characters escape on in the film's final sequence with a faded but unfettered elegance. She is amazing in this film. There is a brooding in the eyes that reveals the deepest pain, even while showing pleasure in simple joys. It is as if the pleasure and the momentary pain go hand in hand. It is a remarkably observed detail of character that flows right out of a desire (expressed in the movie's commentary) for nuancing a Russian sensibility. Having written about Russians myself, and known a few, this is exactly the quality worth striving for. It means that a character's deep sadness and equally her capacity for happiness are never in dispute. One scene which captures this duality with absolute brilliance occurs when someone from her old world in Russia, now himself reduced to bussing bottles and clearing tables, recognizes the countess in the club. Approaching her with the utmost respect, he reminds her of their childhood times together playing tennis. The slow recognition on her face, the movement through beats of uncertainty to amazement, to joy, to tragic sadness again as he kisses her hand to leave, are breathtaking. The brimming brooding eyes as he moves away speak vividly to all of her losses. It is a master class of "beat" work! The character who ultimately unites our two lost souls is Katya, the daughter of the countess, whose bright alertness to her world makes her an easy pawn in her family's dynamics but also enables her to be freed from them in the end. Played by Madeleine Daly, her red-headed narrow face seems a more likely offshoot of Grushenka, played by Madeleine Potter, the countess' sister-in-law, who is childless and tries hard to drive wedges between mother and daughter. Katya walks through all the worlds of this film: though never seen in the nightclub, she does meet up with and befriend the Fiennes character, and reminds him of his own lost child. She also provides a tie to the other social world of this film which is a family of Jewish immigrants to Shanghai, whose children are a more natural source of companionship for her than her strange family. This exposure helps give her a worldliness that fully ennobles one of the last shots of the film, as she stands staring off the prow of a ship into her own future.

The character who ultimately unites our two lost souls is Katya, the daughter of the countess, whose bright alertness to her world makes her an easy pawn in her family's dynamics but also enables her to be freed from them in the end. Played by Madeleine Daly, her red-headed narrow face seems a more likely offshoot of Grushenka, played by Madeleine Potter, the countess' sister-in-law, who is childless and tries hard to drive wedges between mother and daughter. Katya walks through all the worlds of this film: though never seen in the nightclub, she does meet up with and befriend the Fiennes character, and reminds him of his own lost child. She also provides a tie to the other social world of this film which is a family of Jewish immigrants to Shanghai, whose children are a more natural source of companionship for her than her strange family. This exposure helps give her a worldliness that fully ennobles one of the last shots of the film, as she stands staring off the prow of a ship into her own future. This image at left comes from that same last scene. It represents one of the few moments of near-happiness and transcendence that exists in this film. Our tragedy-sodden characters only find solace with each other through another tragedy, which is the end of the world as they were living it. This is often how it is in life: it often does take the utter decimation of the static place in which we have cemented ourselves, to push us forward, kick us out of the trenches of our own pain. On a boat bound for Macao our characters huddle in the mist and listen to the sounds of a forlorn but hopeful trumpet, now free of the baggage of what was, and off on a new voyage.

This image at left comes from that same last scene. It represents one of the few moments of near-happiness and transcendence that exists in this film. Our tragedy-sodden characters only find solace with each other through another tragedy, which is the end of the world as they were living it. This is often how it is in life: it often does take the utter decimation of the static place in which we have cemented ourselves, to push us forward, kick us out of the trenches of our own pain. On a boat bound for Macao our characters huddle in the mist and listen to the sounds of a forlorn but hopeful trumpet, now free of the baggage of what was, and off on a new voyage.

No comments:

Post a Comment