When I was a young girl in the 70s, visiting my grandparents in Philadelphia, some part of every day was spent watching Julia Child on television. My grandmother sat on the blue sofa at the back of the front room and knitted while she watched, pausing sometimes in the middle of stitches, to pay closer attention. My grandmother herself had spent some time at the Cordon Bleu cooking school in Paris. Later, her passion for Julia shared the stage with an equal fondness for Jacques Pepin, whose 'appy coooking' became as much a favorite expression for Grandma, as 'bon appetit' had been.

When I was a young girl in the 70s, visiting my grandparents in Philadelphia, some part of every day was spent watching Julia Child on television. My grandmother sat on the blue sofa at the back of the front room and knitted while she watched, pausing sometimes in the middle of stitches, to pay closer attention. My grandmother herself had spent some time at the Cordon Bleu cooking school in Paris. Later, her passion for Julia shared the stage with an equal fondness for Jacques Pepin, whose 'appy coooking' became as much a favorite expression for Grandma, as 'bon appetit' had been.If she had lived past 2001, my grandmother would have been 98 on August 7th, which was, coincidentally, the release date of Julie & Julia, Nora Ephron's uneven but entertaining adaptation of Julia Child's memoir and Julie Powell's blog of the year she spent making all of the recipes in Child's opus, Mastering the Art of French Cooking. Today, August 15th, is Julia Child's birthday - she was just a year younger than my grandmother. Like Julia Child and Julie Powell, these two women had nothing in common except their passion for cooking. Julia Child introduced french cuisine to average Americans like my grandmother, and she also radically altered the palette and technique of American restaurant kitchens (something the movie does not get into). The next big wave would be the move to more natural and local eating, but even the goddesses of that movement, like Alice Waters, were in debt to the doyenne of beurre blanc.

As Child's long-devoted husband Paul, Stanley Tucci is perfect, as only he can be. His own comedic timing is different from Streep's - a little more playful and nuanced - but he manages to convey in soft strokes his identities as Mr. Julia, on the one hand, and as a government officer whose career is dwindling, on the other. Even more perfect is Jane Lynch, in a short turn as Child's sister Dorothy. A hugely underappreciated character actor, Lynch made it seem as if these were indeed two women cut of the same pate brisee... her entrance and the subsequent restaurant scene with Streep and Tucci is one of the best sequences in the film. Frances Sternhagen as cookbook legend Irma Rombauer and Linda Emond as Simone Beck, Child's cookbook collaborator, give lovely supportive performances.

As Child's long-devoted husband Paul, Stanley Tucci is perfect, as only he can be. His own comedic timing is different from Streep's - a little more playful and nuanced - but he manages to convey in soft strokes his identities as Mr. Julia, on the one hand, and as a government officer whose career is dwindling, on the other. Even more perfect is Jane Lynch, in a short turn as Child's sister Dorothy. A hugely underappreciated character actor, Lynch made it seem as if these were indeed two women cut of the same pate brisee... her entrance and the subsequent restaurant scene with Streep and Tucci is one of the best sequences in the film. Frances Sternhagen as cookbook legend Irma Rombauer and Linda Emond as Simone Beck, Child's cookbook collaborator, give lovely supportive performances. In her currently running blog on the making of her book and story into the movie, Julie Powell confesses that she has seen the movie six times and still cringes at the parts about herself. I haven't read her original Julia blog, but I'm with her. The film tries to convey a fairy tale American success story in the parlaying of her cooking blog into a hit book. There is much mention of Julia Child having "saved her" from drowning and lifting her sense of self-esteem. Even as much of the current blog as I read tonight when I got home did not convince me that much has changed. She seems incredibly self-deprecating and almost an eerily objective witness to her own public transformation, rather than someone appreciating it from a place of solid emotional growth.

Perhaps this is part of why the emotional journey of Julie Powell in the film is never convincing. A substantial part of the blame can be laid on Ephron's mediocre and disappointing screenplay. She is so much better than this script. Having seen a preview before the film of the next Streep movie, It's Complicated, I found myself daydreaming about what this movie might have been like if Nancy Meyers had made it. Meyers has a genuine gift for comedy as a filmmaker and her own writing never clunks in its transfer to the screen. Something's Gotta Give works entirely because its heavy romanticism is very self-conscious and even pokes fun at itself. This is the central flaw of Ephron's movie: it takes itself way too seriously (while never engaging more than surface emotion.) There is a lot of 'faux depth' in the Powell storyline. Even in the Child sequences, when there is confusion and setback around the publication of the cookbook, the script is laced with oneliners like "your book will change the world". When Stanley Tucci says it, he is able to give it a lovely playful quality that allows us to accept that wretched line. The modern story is not nearly able to pull the same thing off.

Perhaps this is part of why the emotional journey of Julie Powell in the film is never convincing. A substantial part of the blame can be laid on Ephron's mediocre and disappointing screenplay. She is so much better than this script. Having seen a preview before the film of the next Streep movie, It's Complicated, I found myself daydreaming about what this movie might have been like if Nancy Meyers had made it. Meyers has a genuine gift for comedy as a filmmaker and her own writing never clunks in its transfer to the screen. Something's Gotta Give works entirely because its heavy romanticism is very self-conscious and even pokes fun at itself. This is the central flaw of Ephron's movie: it takes itself way too seriously (while never engaging more than surface emotion.) There is a lot of 'faux depth' in the Powell storyline. Even in the Child sequences, when there is confusion and setback around the publication of the cookbook, the script is laced with oneliners like "your book will change the world". When Stanley Tucci says it, he is able to give it a lovely playful quality that allows us to accept that wretched line. The modern story is not nearly able to pull the same thing off.An attempt is made to link the two stories through the common elements of challenge, like rejection and peer pressure. These are never really convincing - they seem arbitrary and obvious. For this reason the film feels much longer than it should be. Without a real dramatic tension, it just seems to drift.

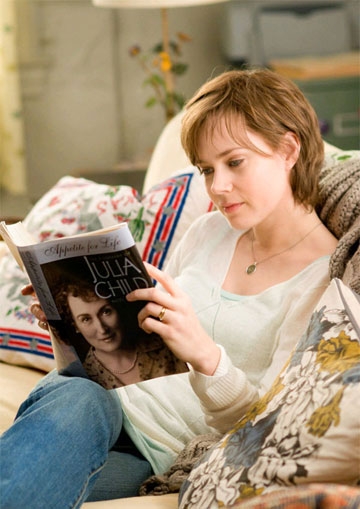

Amy Adams tries hard to make her role deeper than it is, but not even a fine actor like her can pull it off. While Meryl Streep, on the other hand, refines her plunging instincts to be sure and not make Julia seem deeper than she actually was. The irony of this is important and entirely measures the screenplay. Neither actress should have had to work so hard.

2 comments:

The Julie section was for our times -- branding, not living. Ultimately it felt downright bulimic.

Great metaphor and I agree. There was no sense of her having journeyed in the cuisine either - the moments of 'aha' in making her own learnings about cooking - it was all about The Task. The goal. The numbers counting down. The script in these sections sounded more like the pitch or story session discussions of those scenes instead of actual scenes. I kept thinking, "that's the outline, now write the scene".

Post a Comment