The first and only time I have ever been to the Cannes film festival was in 1978. One day on my own, I became lost in the Carlton Hotel on the famed Croisette and accidentally fell in with a party of people leaving the building that turned out to be the cast of Louis Malle's Pretty Baby. Without realising what was happening, I was being snapped at by papparazzi among Susan Sarandon, Keith Carradine and the very young Brooke Shields. Escaping to the crowd, I looked back from its safety at the people I had just been with and understood - for a moment - what it was like to be the focus of that craziness. (Ten years later, while at film school in Los Angeles, I worked briefly as a nanny for Keith Carradine and told him that experience. But even by then, I had come to understand the true cost of belonging to that world.)

The first and only time I have ever been to the Cannes film festival was in 1978. One day on my own, I became lost in the Carlton Hotel on the famed Croisette and accidentally fell in with a party of people leaving the building that turned out to be the cast of Louis Malle's Pretty Baby. Without realising what was happening, I was being snapped at by papparazzi among Susan Sarandon, Keith Carradine and the very young Brooke Shields. Escaping to the crowd, I looked back from its safety at the people I had just been with and understood - for a moment - what it was like to be the focus of that craziness. (Ten years later, while at film school in Los Angeles, I worked briefly as a nanny for Keith Carradine and told him that experience. But even by then, I had come to understand the true cost of belonging to that world.)That year at Cannes, my two friends and myself went to a screening of a movie called 92 Minutes of Yesterday, by a Danish filmmaker. It felt like 700,000 minutes of never-ending eternity. We decided that we had found a new form of torture - being forced to watch a Danish movie! Luckily, I was later reawakened to the country's cinema by Gabriel Axel's Babette's Feast (one of my all time favourite films), and then discovered Lars von Trier in the 90s. There has been no turning back.

Several years ago, I had the chance to interview Lone Scherfig (that's her to the left), who was at TIFF with her film, Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself, set in Glasgow. I was impressed by the deep vein of humour that runs through Wilbur and was equally impressed by her own quick wit and desire to find humour in the midst of even the most tragic stories. I had come to the movie from the quiet lyric depth of her previous film, Italian for Beginners. I asked Scherfig then what had drawn her to making a film set in Scotland. She said she felt an affinity with the Scots, that they were the closest thing to the Danes she had found in Europe.

Several years ago, I had the chance to interview Lone Scherfig (that's her to the left), who was at TIFF with her film, Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself, set in Glasgow. I was impressed by the deep vein of humour that runs through Wilbur and was equally impressed by her own quick wit and desire to find humour in the midst of even the most tragic stories. I had come to the movie from the quiet lyric depth of her previous film, Italian for Beginners. I asked Scherfig then what had drawn her to making a film set in Scotland. She said she felt an affinity with the Scots, that they were the closest thing to the Danes she had found in Europe. Now three of the most gifted Danish filmmakers have come together to create a great Dogme - style challenge. Danes Scherfig and the increasingly exciting Anders Thomas Jensen have created and developed a series of Scots characters which they have offered to three young British filmmakers to make movies with. The project is called Advance Party and the lucky filmmakers selected must use all the characters created, but can do with them what they want. And the movie must be set in Glasgow. The first of the films to emerge from Advance Party is Andrea Arnold's Red Road. Arnold wrote the screenplay and directed the film, an unusual and brilliant depiction of how obssession and grief can lead to awkward but ultimately transcendent encounters. A woman monitors the streets of a community on Closed Circuit TV - hired to look out for crime. A chance sighting leads her to pursue a man who has recently been released from prison. We sense early on that their lives are entwined but we don't find out why or how til we have become deeply entrenched in our heroine's need for the connection. Her decisions, which are unsafe and lead to harrowing circumstances, we adopt and accept without thinking because we feel her sense of desperation. The payoff on the story is not unforseen, but the emotional payoff is. And this, to my mind, is what is marking the best aspect of European cinema right now. Story and emotion are given equal value, but in the end emotion gets the edge - subtly, carefully, and powerfully.

Now three of the most gifted Danish filmmakers have come together to create a great Dogme - style challenge. Danes Scherfig and the increasingly exciting Anders Thomas Jensen have created and developed a series of Scots characters which they have offered to three young British filmmakers to make movies with. The project is called Advance Party and the lucky filmmakers selected must use all the characters created, but can do with them what they want. And the movie must be set in Glasgow. The first of the films to emerge from Advance Party is Andrea Arnold's Red Road. Arnold wrote the screenplay and directed the film, an unusual and brilliant depiction of how obssession and grief can lead to awkward but ultimately transcendent encounters. A woman monitors the streets of a community on Closed Circuit TV - hired to look out for crime. A chance sighting leads her to pursue a man who has recently been released from prison. We sense early on that their lives are entwined but we don't find out why or how til we have become deeply entrenched in our heroine's need for the connection. Her decisions, which are unsafe and lead to harrowing circumstances, we adopt and accept without thinking because we feel her sense of desperation. The payoff on the story is not unforseen, but the emotional payoff is. And this, to my mind, is what is marking the best aspect of European cinema right now. Story and emotion are given equal value, but in the end emotion gets the edge - subtly, carefully, and powerfully. There is also incredibly strong filmmaking here. Red Road created a stir at Cannes and won that festival's Jury prize. The programme book compares Arnold's style to Michael Haneke - whose last year's Cache had quiet impact. I would compare her more to Ken Loach, whose previous films have also been set in Glasgow - I think particularly of the mesmerizing power of My Name is Joe and of course Sixteen. The lead actor in Sixteen was Martin Compston, who is also in Red Road. The movie probes psychological truths: the reason good people pursue dangerous opportunities - which is usually to wrestle their demons to the mat. The choices are slow and subtle, but escalate rapidly when put together. In the end, there is healing, and not the kind that hits us on the head. Red Road is a must see whenever it finds North American release.

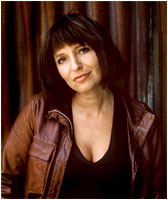

But even more beautiful is the film I just saw, by Danish helmer Susanne Bier (that's her at the top), After the Wedding. This film was actually written by Anders Thomas Jensen and is an exquisite journey to the heart of several huge themes: how we choose and create families; who we really belong to; what calls us ultimately to our future - idealism or identity. A man returns to Denmark to get blanket approval of a new project he is working on in India, only to discover his own past unexpectedly waiting for him. Like Scherfig's Wilbur, the characters in this movie appear to reverse roles - people we thought were good turn out to have done bad things and the bad people are not so bad after all. Then it all evens out as choices get made and the playing field becomes leveled. People own and disown each other and make their peace, and grief becomes three-dimensional. It is an incredibly beautiful film by the always astonishing Bier with gorgeous writing and performances. Call it 'Susanne's Feast' - in memory of that other great Danish film, made back in the days when I thought it wasn't possible!

But even more beautiful is the film I just saw, by Danish helmer Susanne Bier (that's her at the top), After the Wedding. This film was actually written by Anders Thomas Jensen and is an exquisite journey to the heart of several huge themes: how we choose and create families; who we really belong to; what calls us ultimately to our future - idealism or identity. A man returns to Denmark to get blanket approval of a new project he is working on in India, only to discover his own past unexpectedly waiting for him. Like Scherfig's Wilbur, the characters in this movie appear to reverse roles - people we thought were good turn out to have done bad things and the bad people are not so bad after all. Then it all evens out as choices get made and the playing field becomes leveled. People own and disown each other and make their peace, and grief becomes three-dimensional. It is an incredibly beautiful film by the always astonishing Bier with gorgeous writing and performances. Call it 'Susanne's Feast' - in memory of that other great Danish film, made back in the days when I thought it wasn't possible!

No comments:

Post a Comment