Choosing the best films of the Festival experience is always incredibly subjective. As usual (see posts from last year) I did not see the films that have won the majority of awards, with notable exception: Jennifer Baichwal's powerful Manufactured Landscapes (pictured here) which has won the CITY-TV Award for Outstanding Canadian Feature. Numbered among the prize winners also is a film I tried hard to see and missed: Takva: A Man's Fear of God. Too bad.

Choosing the best films of the Festival experience is always incredibly subjective. As usual (see posts from last year) I did not see the films that have won the majority of awards, with notable exception: Jennifer Baichwal's powerful Manufactured Landscapes (pictured here) which has won the CITY-TV Award for Outstanding Canadian Feature. Numbered among the prize winners also is a film I tried hard to see and missed: Takva: A Man's Fear of God. Too bad.Then there were films I saw only partially - by slipping in for the last half hour, like Sarah Polley's Away From Her. That half hour, however, was so lovely that I am now really anxious to see the rest of it.

The films that seem the least interesting the day after the festival ends often bear out very differently over time. As images settle, the vision becomes clearer and the ideas come into focus. A month from now I may have changed my mind and other films I saw may have in fact floated to the top. Sometimes filmmakers are living up to heavy hitting previous films in my experience, and then, because they don't seem as glorious, I give them less weight in my mind than they deserve. This year's example is Robert Guediguian's Voyage en Armenie, a film critics universally loved and which the public clearly enjoyed and I just couldn't raise to the bar set by his previous love letter, Marijo et ses deux amours. I recognize the film as accomplished and resonant, but it's just not the same. Similarly, Kenneth Branagh's The Magic Flute has been growing steadily for me over the past week - and there was much of it I already really loved. It hasn't made my ten best but check back in a few months time.

The films that seem the least interesting the day after the festival ends often bear out very differently over time. As images settle, the vision becomes clearer and the ideas come into focus. A month from now I may have changed my mind and other films I saw may have in fact floated to the top. Sometimes filmmakers are living up to heavy hitting previous films in my experience, and then, because they don't seem as glorious, I give them less weight in my mind than they deserve. This year's example is Robert Guediguian's Voyage en Armenie, a film critics universally loved and which the public clearly enjoyed and I just couldn't raise to the bar set by his previous love letter, Marijo et ses deux amours. I recognize the film as accomplished and resonant, but it's just not the same. Similarly, Kenneth Branagh's The Magic Flute has been growing steadily for me over the past week - and there was much of it I already really loved. It hasn't made my ten best but check back in a few months time.Here then, for right now, are the films which impacted me most, both personally and in terms of their vision and filmmaking expression.

1. After the Wedding, Susanne Bier, Denmark

1. After the Wedding, Susanne Bier, DenmarkIn my previous post, I talk about the emergence of Danish filmmaking in recent years as the strongest voice in European cinema. Susanne Bier's emotionally fine-tuned essay on families, belonging and identity uses contrasting environments (India/Denmark) and carefully contemplative shots to help us linger in the hearts and minds of her characters, even after the camera has moved on. The non-linear jump-cutting editing style of the film is neither pretentious nor in our face, but truly serves the disjointed and fragmentary sense of time and space that occurs in the midst of emotional upheaval. Poetic, lyrical, and utterly compelling.

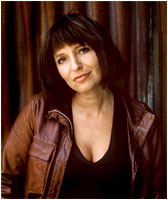

2. Manufactured Landscapes, Jennifer Baichwal, Canada

With this deeply affecting and haunting film, Jennifer Baichwal has done something that rarely occurs in the documentary form: she has celebrated the work of an artist, while liberating his vision and giving it a cinematic expression. For those who have seen Edward Burtynsky's astonishing photographs (that's one at the top) of industrial landscapes, and experienced the ethical push-pull of responding to their beauty, this film will ground you. It is reminiscent of the work of Thomas Riedelsheimer (Rivers and Tides; Touch the Sound) in its capacity to allow the subject to simply breathe on its own. The opening shot, which proceeds along the endless rows of wo/manned manufacturing stations in a single take, has iconographic power and sets up everything that is to come. Nearly eight minutes long, it is almost more than we can sustain and all without a single spoken word or commentary. By far one of the best documentaries of recent times. It is being released in October - so go see it!

3. Babel, Alejandro Gonzalez Inarittu, USA

I always hesitate to program into my schedule movies which I know will be released and I usually hesitate to include them in my best of lists. But there's no question here. This is superlative filmmaking, and this director's finest work to date. Some sequences are stronger than others, or I would put it at number one. (see post below)

4. La Coupure, Jean Chateauvert, Canada

4. La Coupure, Jean Chateauvert, CanadaIt is such a pleasure to be putting Canadian films near to the top - that doesn't happen every year. This is an exquisitely tender film about a love relationship among a brother and sister that has evolved to the fullest place it can have in regular life. So many things were unusual about the subtly nuanced screenplay - from the intensely passionate (but not sensational) sex that opens the film to the fact that almost everyone in the family has figured it out and adjusted with varying degrees of acceptance, denial, understanding, anger, frustration and pain. Quiet and enormous, with very little spoken word, it allows us to ache with our main characters and long for them to somehow find a way to make it all work - right to the finish line. It also crosses generational lines in its ways of responding, and not as we might predict. A filmmaker to watch.

5. L'Esprit des Lieux, Catherine Martin, Canada

5. L'Esprit des Lieux, Catherine Martin, CanadaLike Baichwal, Catherine Martin has created a visual poem, but this time with peaceful images. An ode to the lost ways of life in the Charlevoix regions of Quebec, it offered landscape that was entirely new to me and deeply affecting. Similar to Baichwal, she is working in the context of photography - this time by Gabor Szilasi, whose images of the region in the 70s are a testament its vibrant life. Martin contrasts these pictures not only with contemporary versions of the images, but with beautifully constructed and carefully posed still life portraits of her interviewed subjects. It is these portrait shots, often held a minute or longer, that become so deeply affecting as we realise that with this film another marker has occurred, from which the life can be measured again in another thirty years.

6. Kristall, by Christoph Girardet and Matthias Muller of Germany and Roads of Kiarostami by Iranian master Abbas Kiarostami. These two shorts from the Wavelengths programme are beautifully constructed celebrations of previously captured image, reinvented (see a theme emerging folks?). Kristall takes footage from Hollywood films that revolve around mirrors and treats it with distortion or heightened illumination. It's the way they have been sewn together that is most impressive - we see images of longing and appreciative looks into mirrors, then sadness and despair, then mirrors breaking. The Kiarostami work lived up to what I had anticipated (see post below) and is almost the inverse of Jennifer Baichwal's film by providing landscape at once familiar and unremarkable, but presented in such a loving way that the filmmaker's affiintiy for land and country seem more apparent than in any of his other films. Like a warm bath, the black and white images of trees gently moving in isolation along long winding curving roads have stayed with me in the most comforting way.

6. Kristall, by Christoph Girardet and Matthias Muller of Germany and Roads of Kiarostami by Iranian master Abbas Kiarostami. These two shorts from the Wavelengths programme are beautifully constructed celebrations of previously captured image, reinvented (see a theme emerging folks?). Kristall takes footage from Hollywood films that revolve around mirrors and treats it with distortion or heightened illumination. It's the way they have been sewn together that is most impressive - we see images of longing and appreciative looks into mirrors, then sadness and despair, then mirrors breaking. The Kiarostami work lived up to what I had anticipated (see post below) and is almost the inverse of Jennifer Baichwal's film by providing landscape at once familiar and unremarkable, but presented in such a loving way that the filmmaker's affiintiy for land and country seem more apparent than in any of his other films. Like a warm bath, the black and white images of trees gently moving in isolation along long winding curving roads have stayed with me in the most comforting way. 7. "Place des Victoires" segment from Paris je T'aime, Nobuhiro Suwa, France

7. "Place des Victoires" segment from Paris je T'aime, Nobuhiro Suwa, FranceThe transcendent face of Juliette Binoche as a mother adjusting to the loss of a child remains my favourite image of this festival. The dark tones and melancholic emotional lines, expressed in yellows and blacks and greens, have become a signature part of this Japanese filmmaker's style, often contrasted by brightly lit environments. (see posts below) Suwa's Un Couple Parfait from last year's festival is screening at Cinematheque in November. Don't miss it.

8. Volver, Pedro Almodovar, Spain

Penelope Cruz's tragicomic performance as the woman sandwiched in the pain of everyone around her just might be the best performance I saw. The range of emotion she carries through every moment (see post below) is the lynchpin of the movie and yet another loving tribute of a master filmmaker to the world of women. A carefully crafted screenplay tugged into life with a clear visionary style, this is yet another quiet masterpiece from a film festival favourite.

9. Red Road, Andrea Arnold, UK/Denmark

Working with Danish-created characters, but set in Scotland (see previous post), this film about facing and overcoming past mistakes is probably among the most inventive films I saw this year. The premise is engaged in a narratively non-traditional way by allowing the character to reveal to us her own situation as and when she's ready and not presenting it to us as part of exposition. It also makes an interesting statement about voyeurism as healing! Winner of the Oscar for Short Subject filmmaking for her film Wasp, this highly anticipated filmmaker won the Jury Prize at Cannes with Red Road. For once, juries and voters get it right.

10. Stranger than Fiction, Marc Forster, USA

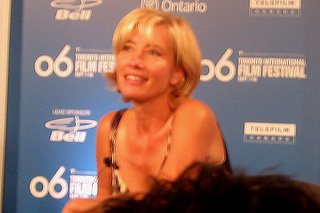

10. Stranger than Fiction, Marc Forster, USAThis movie is about to hit theatres and hit big. Cleverly written, it is that rare commercial Hollywood discovery: an intelligently written, truly funny, comedy. With great performances by Will Ferrell, Emma Thompson, Maggie Gyllenhall and Dustin Hoffman, it is worth the drive, the parking, the babysiter and the cost of popcorn that it takes to be in the commercial cinema these days. Lofty praise indeed!

Honorable Mention:

Quelques Jours en Septembre, Santiago Amigorena, France/Italy

Quelques Jours en Septembre, Santiago Amigorena, France/ItalyA strangely funny and completely engrossing thriller noir set in Paris and Venice, it features Juliette Binoche in her most unusual casting to date as a spy-teacher out to protect the interests of spy-in-hiding Nick Nolte. I am so transparently a Binoche addict in this blog that I make no attempt to hide my clear prejudice for liking the movie but she is sometimes cast badly and I had my doubts going in. John Turturro is hilarious as a hit man who needs to speak to his shrink before and after each 'job' (in good French too!) and the screenplay is clever and unexpectedly resonant. This one will likely float higher as time moves on.

The Wind That Shakes the Barley, Ken Loach, UK

This movie suffers from being positioned at the very beginning of my festival experience, and therefore some thirty films ago, but its quiet, provocative tribute to the Irish independence movement hasn't left me. With gently affecting performances from Orla Fitzgerald and Cillian Murphy, it deserves every accolade that has come its way. Another compelling canvass from a master visual artist.