|

| Carol refers to Therese in the movie as 'my angel, flung out of space'. But it is the film itself which seems to float in a liminal place. |

Ever since I first stumbled upon news of Carol some time last winter, I have been sort of leaning toward it in a posture of waiting. I joined the fan pages (Carol has one of the best-maintained and most creative fan pages of any movie I've seen). I followed every clip or behind-scenes mini doc that turned up on youtube, including those blurry heartfelt but roughly assembled tributes by fans overusing second or third generation bootlegged footage, while a late 40s ballad croons. The list of these 40s and 50s standards that run in the background of the movie was released early on and I bought each tune separately, compiling my own soundtrack and putting it on in my car, learning all the songs; wonderful songs by Billie Holiday and Helen Foster and Jo Stafford. I took away with me on summer holiday The Price of Salt, the Patricia Highsmith novel she wrote as Claire Morgan, on which the movie is based. Rereading it brought back the youthful memories of the first time that story came into my life and the people associated with that. In May, I waited on Twitter for the first Cannes reviews to drift in. Traveling that day, I got out of the car and stood by a field with my phone at the exact hour that I knew the first press screening came down. Refreshing my feed, I waited, while a cow stared. Then the accolades started to come: 140 character rhapsodic bleats, for me like the first transmissions of men on the moon. When it didn't come to TIFF, I observed longingly as it played through literally every other fall festival on two continents. And then, in late December, it finally arrived in Toronto where I have now seen it. Twice.

And although I have always been predisposed to love it, I had a sense of art entering the veins and swimming upstream. I had that experience in 1993 when I first saw Kieslowski's Three Colours: Blue. I had it in 2011 with Terrence Malick's The Tree of Life. And now I've had it again.

|

| One of the best B-rolls from any movie any time, underscores the low-budget simplicity of the filmmaking. Go here to see the video. |

Many of them want to reach first of all for the obvious comparison to Todd Haynes' earlier film Far From Heaven. I did this too, in my first post on Facebook back in May before I had seen it, because at a glance and without knowing, that's what you think you're going to get. But it doesn't actually work - that comparison. (As the director has tried to say a number of times, including in this NYFF onstage interview.) What the two movies have in common is their social context - the 1950s, but that's it. Far From Heaven was an homage to the late 50's Douglas Sirk robustly colourful dramas of that era. By contrast, inspiration is actually owed in Carol to the early 50s/late 40s gritty landscapes and portraits of the photographers of the post-war period. Haynes has said that he looked at the work of Saul Leiter, and yes! this is exactly what we see - both the earlier painter version of Leiter and the later fashion photographer version. (Here is a good brief primer on Leiter.)

|

| The use of colour in some scenes evokes the colour work of photographer Helen Levitt and the late period of Vivian Maier. |

And yet somehow the movie avoids feeling like a pastiche, a survey of art styles. Here credit goes to Production Designer Judy Becker and Costume Designer Sandy Powell. Holy smoke curling gently from a lit cigarette. It is hard to imagine a more compatibly unified design sensibility. While the sets are muted in a late 40s post-war grey-brown, so real that you feel you can reach out and touch the steel leg of the motel breakfast table, the contrasting energy of Carol's chic ensembles allows a feeling of relief and animation, even while the richer woman's wardrobe is elegantly reserved. The fur coat is the only opulent moment and even the sandy colour here is perfect. Moving among odd looking dolls at the toy department where Therese works, Carol is indeed like a waft of perfume with a woman attached.

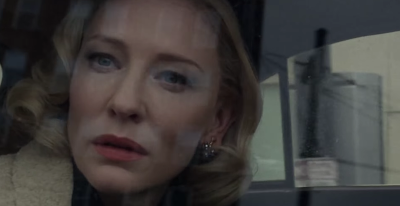

Blanchett's nuanced performance is measured, rather than mannered, a very delicate thing to accomplish in a period-drenched movie like this one and a choice few other actors would be capable of. Her performance is so nuanced and brilliantly layered that many might miss these subtleties, looking for more overt signs of 'acting'. Or they might mistake her stylized choices of character behaviour for something contrived. But Blanchett has always had the extraordinary capacity to hold contrasting styles in one performance and orchestrate them powerfully. I remember seeing her in a Sydney Theatre Company (at BAM) performance of Hedda Gabler near-exactly ten years ago in which she held both the manipulative and vulnerable sides of the brittle title character in an equally firm grasp. I wrote about her capacity for this kind of brilliance, even then.

|

| Rooney Mara's natural innocence as Therese moves in the context of the porcelain dolls she half-heartedly sells in the film's opening scene. |

The extraordinary gaze each gives the other in the final moment of the film is one of the most love-drenched and also soberest endings to a romantic movie ever. It is exactly the moment of arrival into their own space. In the goodbye letter she had written earlier, Carol even then looks ahead to some unknown moment in time of reunion. "I want you to imagine me there to greet you like the morning sky, our lives stretched out ahead of us, a perpetual sunrise." By the time that possibility actually arrives, we the audience have completely forgotten that she had dared to dream of it. But Therese has not. Mara's moment of the character making that breathstealing walk in the restaurant is a way of showing us that Therese has hung on those lines of Carol's, even as she has in all outward appearances, let go of her. And just as Kristen Stewart surprised us in Clouds of Sils Maria, Mara, who has a much longer track record of impressive performances, still surprises us in Carol. (Interesting, too, that both these performances come as the young actors are playing ordinary young women, watched and loved by older more famous female actors playing established doyennes.)

|

| Composer Carter Burwell, with producer Elizabeth Karlsen and screenwriter Phyllis Nagy at the Hamptons Film Festival where Burwell's work was awarded. |

|

| The eroticism is gentle and spare, just to let us know it is there, and landing on the side of tenderness. Yet another bravely right decision. |

It is this slightly brittle edge that has caused some to find the movie a bit cold. If your heart is beating with the women, there is no chance of being cold, even for a second. The intimacy is all emotional, although we get the nude scene kind too. But that one love scene seems almost intended to be an abbreviation, so that the audience will not focus on it too much. In fact, there are other scenes that accomplish the tenderness of intimacy more vividly. After a terrible event that might have separated them, Carol tells Therese she doesn't have to sleep in the other bed in the new hotel room. Even fully clothed, as Therese comes into Carol's arms, she disappears under her in a way we all dream of being embraced -- with such deep love, more important in this moment, than the desire that got them into trouble.

|

| There are many moments when Judy Becker's production design acts like a visual 'score' of the movie's deepest underlying themes. |

|

| The two leads, as photographed by Wally Skalij for the L.A. Times |

|

| "It's still an unnatural and overdetermined moment at Cannes. It's like launching something from the top of a wedding cake," says Todd Haynes, in the best joint interview, done on the morning after the Cannes debut, by Nigel Smith of Indiewire. |

Although most queer criticism of the movie has lauded and welcomed its breath of fresh air, there has also been a whiff of critique towards the movie because it is not agenda'd enough. In this way, the film reveals the agenda of the respondents, because it has no agenda itself. This kind of writing misses the point that the brilliance of the movie (which includes at least three openly gay artists in its main creative team), is that it can convey the experience of human love in general, while also detailing lesbian relationship in particular, and very specifically, lesbian relationship in the 1950s. It is a hat trick of cinematic integration.

|

| Many of their scenes occur while they themselves are en route. The result is a sense that we are voyaging with them, as uncertain as they are about how it will all end. |

Eventually, in the scene I've described, Carol pulls the car over and firmly reassures Therese with clarity and also love. Blanchett and Mara know how to stay reserved so that we get a chance to feel it, instead of watching them feel it for us. But there is a thread of the unknown also still there. The underlying preoccupations of a woman torn by love for her child and love for a lover, who knows as she drives and smokes, that her life is not going to be about choosing between them, but about how not to lose both. Then there is the woman riding in the passenger seat who has suddenly understood that her failed personal sense of passivity has in fact driven events. Her incapacity to say no when she should (a beautiful character-writing detail) has led to more moral responsibility than she has ever wanted to assume.

|

| In an "anatomy of a scene" video for The New York Times, Haynes explains how he alternates static shots with two moving shots at the end of the scene in which the women first meet, allowing a sense of emotion now in play. (Go here to see the entire video.) |

|

| The last two shots of the film have been given away in all the trailers, but they still manage to be electrifying when they actually occur. |