The Jewish Museum in New York is currently showing a modernist, unconventional exhibition on the theatrical life of Sarah Bernhardt. It begins with a large digital television looping footage of Marilyn Monroe (surely the antithesis to Sarah Bernhardt) excerpted in the scene from All About Eve in which she laments that her skills as an actor are limited to pushing toothpaste. She longs to be the real thing, like Sarah Bernhardt, and wonders aloud how magnificent the French legendary actress must have been.

It is a bit bizarre as a way to begin a curated journey through Bernhardt’s achievement but the rest of the exhibition bears the style out with bright neon lighting, modernist glass box display cases and television sets with rare footage of the actress lined up along a wall.

The Felix Nadar portraits of Bernhardt on display capture a young actress of 20, long before her prime, gazing with a kind of seductive insouciance at the camera or slightly off-camera, radiating all she has to come and appearing neither coy nor committed about it.

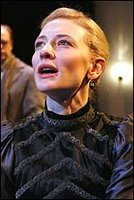

The Felix Nadar portraits of Bernhardt on display capture a young actress of 20, long before her prime, gazing with a kind of seductive insouciance at the camera or slightly off-camera, radiating all she has to come and appearing neither coy nor committed about it.The look was powerfully familiar. I had just the night before seen Cate Blanchett in the Brooklyn Academy of Music-imported Sydney Theatre Company production of Hedda Gabler

and was struck by the similarity in the two actresses. Stripped of her frizzy mane, the French diva has nearly the same face as the Aussie beauty. Blanchett’s is slightly narrower but both faces are wide open and show slim almond-shaped eyes.

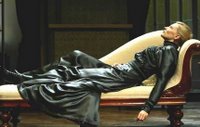

The Bernhardt exhibition evolves into a series of many images of Sarah draped on divans and sofas in one tragic role or another. Similarly, In Robyn Nevin’s staging of Hedda Gabler, Blanchett strikes many such dramatically reclining poses. In fact, the BAM production very bravely emphasizes a highly measured style: the whole form is one of accented dramatization, including melodramatic scoring that thunders at the emotional highpoints and over scene changes, choices most theatre companies would run from. It echoes what has since come to be kitch about melodrama - the organ music of radio serials, the single dramatic notes of early television soaps.

At the same time, however, the actors are embracing the naturalism that Ibsen had turned to by the time of Hedda Gabler. They overlap their dialogue, allow wonderful long silences and gestures and looks that can be seen only by those privy to them.

At the same time, however, the actors are embracing the naturalism that Ibsen had turned to by the time of Hedda Gabler. They overlap their dialogue, allow wonderful long silences and gestures and looks that can be seen only by those privy to them.It is this marriage of high style and naturalism that has cost the show some of its more highbrow critics in New York who seem bewildered how to respond to it. In the post-Actor's Studio method acting-influenced American (and particularly New York) theatre world, the goal is usually to use high style for the post-modern or the absurd (as expressed for instance in the work of The Wooster Group, another Brooklyn-based enclave), but not for a work of naturalism. Because this production does not feel comfortable to some critics, there has been a tendency to blame it on the adaptation by Andrew Upton, or the direction by Robyn Nevin.

They are wrong. Upton and Nevin have made radical choices that are a nod to the true avant-garde of theatre, as their Ibsen counterparts would have experienced it. By placing the naturalistic psychological world of Hedda in a highly stylized melodramatic form, they have drawn attention to the tension, not only of Ibsen’s theatrical times, but of women in the society of those times. They have made us truly uncomfortable, not because of content (which no longer surprises us) but because of the contrasting nature of form. We the audience are ready to judge quickly how the show is working by sliding the work into a familiar context and then sitting back to appreciate it (or not as the case may be). Nevin and Upton make that almost impossible.

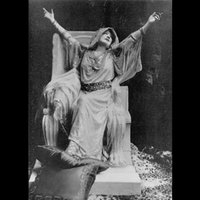

Sarah Bernhardt was the same kind of radical. The genius of Bernhardt were her moments of intense realism and naturalism, the ‘avant’ness she would bring to very formalized classical ‘garde’ acting tradition. Amid the grand body language necessary for a tragedy like Hamlet or La Dame aux Camellias, she would offer a look or a small gesture that would bring the subtext home as nothing else could and make a character suddenly three or six-dimensionally deep. She lifted theatre acting out of its rigid antecedents and into the naturalistic new age. But she accomplished it by living both simultaneously. It was the marriage of these two techniques that gave Bernhardt her signature style. Classically trained body, and piercing, momentary truthful lyricism in expression. This was her way of coping with her times and her world. We could not possibly end up calling her a naturalist, but she paved the way.

Sarah Bernhardt was the same kind of radical. The genius of Bernhardt were her moments of intense realism and naturalism, the ‘avant’ness she would bring to very formalized classical ‘garde’ acting tradition. Amid the grand body language necessary for a tragedy like Hamlet or La Dame aux Camellias, she would offer a look or a small gesture that would bring the subtext home as nothing else could and make a character suddenly three or six-dimensionally deep. She lifted theatre acting out of its rigid antecedents and into the naturalistic new age. But she accomplished it by living both simultaneously. It was the marriage of these two techniques that gave Bernhardt her signature style. Classically trained body, and piercing, momentary truthful lyricism in expression. This was her way of coping with her times and her world. We could not possibly end up calling her a naturalist, but she paved the way.In Hedda Gabler, Cate Blanchett reclines theatrically, steps off one area of the stage to another, leading with the hip and the body arched backwards, walking grandly, parading even as the music crashes and upholds her emotion. What is she doing?, the naturalist thinks. She is following Upton and Nevin’s lead by allowing the naturalism of Ibsen’s play to be trapped in a theatrical tradition of formal melodrama. Then later, she gives us moments of such sudden haunting piercing realism, that the soul of the character is suddenly bared before us. In this combination of styles, she is modelling Bernhardt but in a way many actors today would not choose.

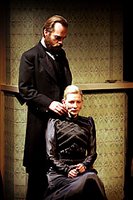

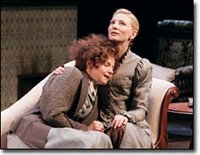

At the play’s finale, Judge Brack lasciviously caresses her neck and shoulder and then lets go, making clear her future as his mistress. (This picture here is from the Sydney production; in New York Blanchett is seated on a sofa allowing greater room for reaction.) In the moment of Brack's letting go, Blanchett’s body curls uncontrollably forward in relief and simultaneous agony. Then her face slowly raises toward us, a contortion of heretofore unseen capacity for pain. This is the moment of death, not the gunshot. This curl forward of the body and lifting of the face signifies all that has been and all that will come. Behind the back of all the characters, we see the crashing knowledge of her own deeds, her own inevitable punishing future. The heroine is speaking only to us - with her face and her body. This is exactly what theatre should be.

At the play’s finale, Judge Brack lasciviously caresses her neck and shoulder and then lets go, making clear her future as his mistress. (This picture here is from the Sydney production; in New York Blanchett is seated on a sofa allowing greater room for reaction.) In the moment of Brack's letting go, Blanchett’s body curls uncontrollably forward in relief and simultaneous agony. Then her face slowly raises toward us, a contortion of heretofore unseen capacity for pain. This is the moment of death, not the gunshot. This curl forward of the body and lifting of the face signifies all that has been and all that will come. Behind the back of all the characters, we see the crashing knowledge of her own deeds, her own inevitable punishing future. The heroine is speaking only to us - with her face and her body. This is exactly what theatre should be.The expression on Blanchett’s frozen face makes clear her decision in a way no stage direction could offer. It has nothing to do with adaptation of text and very little with staging. But the moment’s intensity and strange incongruity validates the production’s controversial choice of actually seeing the suicide, instead of having it offstage. By putting the death onstage, we are returned to the classical and melodramatic style. In a way, it symbolizes Hedda’s dilemma: a woman ahead of her time, trapped in the strictures of her own times. It also shadows the dynamic of the era of theatricality for Bernhardt and Ibsen: their desire for naturalism battles the pervading norm of classicism so heightened it had become melodrama. In the end, for now, melodrama reigns. It would take Chekhov to overthrow that balance.

In an era of theatre naturalism, there is no real need for an actor to revert to a style of high manner or affectation in an Ibsen play. That Blanchett chooses to do so as part of the texture of her work, is uncannily brilliant, and she accomplishes that balance between melodrama and naturalism with an astonishing craft. Having spent most of the play disliking Hedda, intensely, we the audience suddenly ‘get’ her and have profound empathy for her, exactly at the moment it is too late. In doing so, we become participants in the forces that lead to her fate. A more typical approach to the role would be to present her as distasteful but giving us moments of sympathizing with her, particularly through her attachment to Lovborg, her one-time lover. In Blanchett’s performance we find her cold even to him. It’s not until she burns his manuscript that we feel the underlying depth of her passion for him but we are torn because she is destroying his work.

In an era of theatre naturalism, there is no real need for an actor to revert to a style of high manner or affectation in an Ibsen play. That Blanchett chooses to do so as part of the texture of her work, is uncannily brilliant, and she accomplishes that balance between melodrama and naturalism with an astonishing craft. Having spent most of the play disliking Hedda, intensely, we the audience suddenly ‘get’ her and have profound empathy for her, exactly at the moment it is too late. In doing so, we become participants in the forces that lead to her fate. A more typical approach to the role would be to present her as distasteful but giving us moments of sympathizing with her, particularly through her attachment to Lovborg, her one-time lover. In Blanchett’s performance we find her cold even to him. It’s not until she burns his manuscript that we feel the underlying depth of her passion for him but we are torn because she is destroying his work. It is that slippery slope that Blanchett guides us down so expertly. In the act of Hedda’s greatest cruelty, we have a window to her soul. As the events escalate rapidly, she continues to blossom in her pained self-awareness and we by the same degrees more deeply understand her and know that it’s too late. It’s like watching a train wreck. And by this time, the actress has subtly converted from the heightened theatricality of body language to the piercing moments of small truthful realism.

At the performance I attended of Hedda Gabler, the second last of the run, I was seated by outrageous fortune next to Meryl Streep and very near to Jane Fonda. Arguably among the finest actors of their respective generations, their level of engagement in watching Blanchett furthered that wonder in me at the inevitable evolution of theatrical influences. The degrees of separation are keen here: it was Fonda, (an Actor’s Studio trained artist) who declared in Ms. Magazine that Meryl Streep (more classically trained at Yale) would surely become the actress of the next generation, after working with her in only a handful of scenes in the movie Julia in the mid-70s. It was Fonda’s declaration, in part, that drew attention to Streep in Hollywood beyond the world of her burgeoning New York career. Bizarrely, on this Saturday night in March, the two women appeared unaware of each other’s proximity in the theatre, and so the lace-like web of connection was noticed only by an observer like me.

At the performance I attended of Hedda Gabler, the second last of the run, I was seated by outrageous fortune next to Meryl Streep and very near to Jane Fonda. Arguably among the finest actors of their respective generations, their level of engagement in watching Blanchett furthered that wonder in me at the inevitable evolution of theatrical influences. The degrees of separation are keen here: it was Fonda, (an Actor’s Studio trained artist) who declared in Ms. Magazine that Meryl Streep (more classically trained at Yale) would surely become the actress of the next generation, after working with her in only a handful of scenes in the movie Julia in the mid-70s. It was Fonda’s declaration, in part, that drew attention to Streep in Hollywood beyond the world of her burgeoning New York career. Bizarrely, on this Saturday night in March, the two women appeared unaware of each other’s proximity in the theatre, and so the lace-like web of connection was noticed only by an observer like me. There is a handkerchief on display at the Jewish Museum whose white linen is lettered with “Sarah” in embossed stitching. The handkerchief belonged to Bernhardt and in a great tradition of the theatre is being passed forward to great women actors. It currently belongs to Cherry Jones, who surely deserves it. But if it had passed to Blanchett a circle would have been completed. Bernhardt’s handkerchief came to Ute Hagen, who passed it to Helen Hayes who gave it to Julie Harris who gave it to Susan Strasberg who gave it to Cherry Jones. Almost all of these actors are Method-inspired if not trained performers, that is to say inheritors of Chekhov, of pure naturalism. But the spiritual inheritance of Bernhardt, the capacity to hold both classicism and naturalism in the same performance is alive in the face of Blanchett. It is alive in any marriage of style that holds the ‘garde’ and looks ahead. Of all these actors, only Streep would know how to combine these forms and have the skill to do it.

Given the existing synchronicities, it’s possible too that Bernhardt and Blanchett’s descendent was also somewhere in that audience. Perhaps looking on in wonder, conceiving her own ideas about convention and new wave, but in the meantime immeasurably impacted by the moment of Hedda’s death-like swoon.

Given the existing synchronicities, it’s possible too that Bernhardt and Blanchett’s descendent was also somewhere in that audience. Perhaps looking on in wonder, conceiving her own ideas about convention and new wave, but in the meantime immeasurably impacted by the moment of Hedda’s death-like swoon.